Zidoun-Bossuyt gallery is pleased to announce the first exhibition of British artist Danny Fox.

Preview on Wednesday March 14, 2018 from 6pm in presence of the artist.

PRESS RELEASE

The history of Skid Row in Downtown Los Angeles, where Danny Fox works and which informs Blood Spots on Apple Flesh, pivots on the stories of migrants. Formerly an agricultural center, the 54-block area was transformed by railroads in the 1870s, becoming a hub for recent arrivals with its brothels, bars, and seedy hotels.[1] Throughout the twentieth century, the district welcomed those displaced by the currents of history. More than 10,000 homeless lived there during the Great Depression; in the 1960s, returning Vietnam veterans with addiction came to its treatment centers. Today, Skid Row has one of the country’s largest consistent homeless populations.[2] Its character has been forged by newly arrived young men, often immigrants or travelers looking for a new start. Fox, a Cornwall native who arrived in Los Angeles in 2015 from England, on the chance meeting of painter Henry Taylor in a pub, fits squarely into this narrative. His paintings, which often train an eye on Skid Row’s inhabitants and rituals, entwine the brutality of contemporary life with idealized historical imagery.

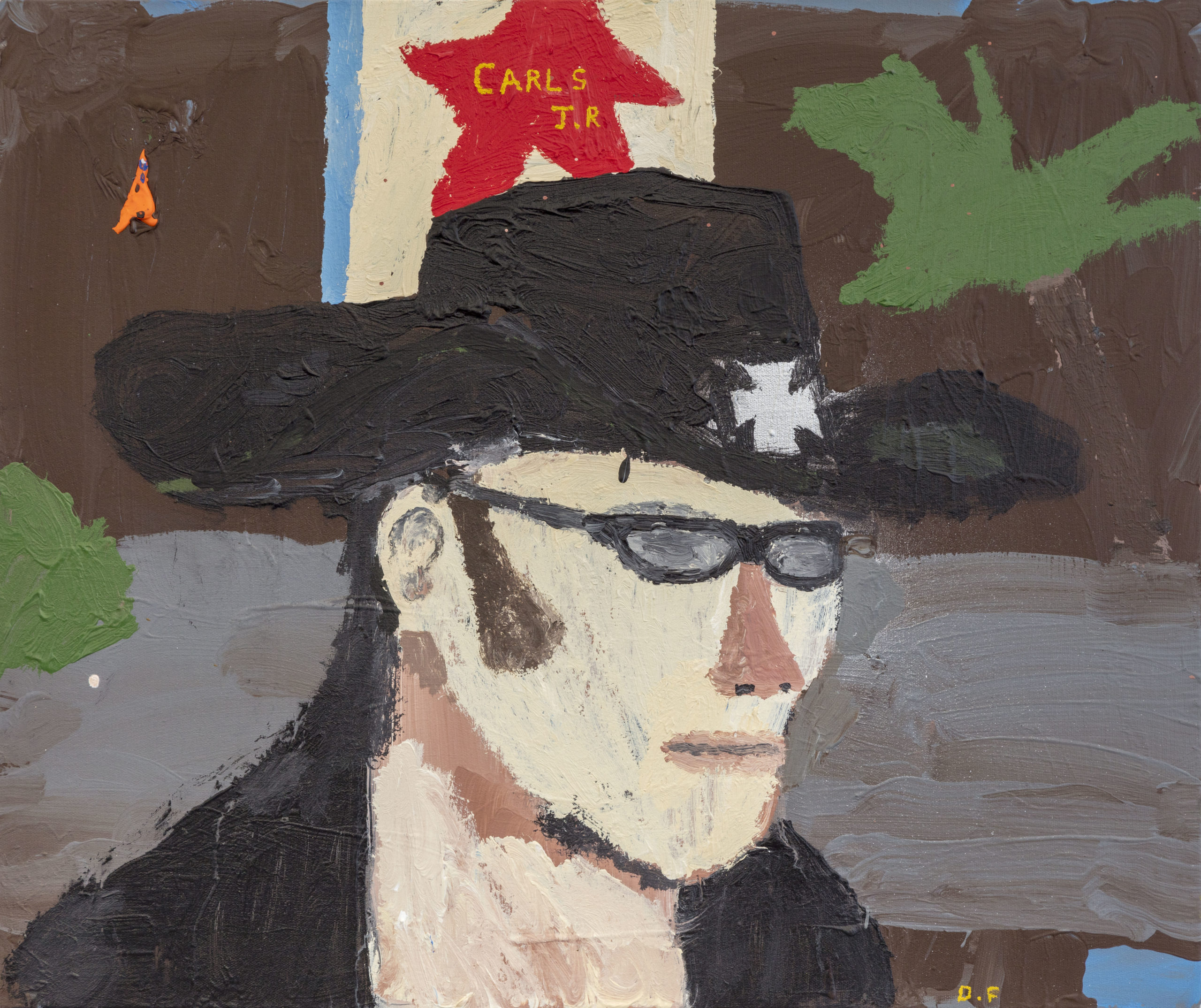

Like Taylor, Fox relies on a raw, unfiltered style of painting that draws attention to the act of making itself. In various works in Blood Spots on Apple Flesh, Fox looks toward Victorian icons—namely, David Livingstone and the prodigal son lithographs of the Kellogg Brothers, celebrated nineteenth-century American lithographers—realized through flashes of his immediate surroundings. These famed stories of travelers are captured in the present, both metaphorically and figuratively, as Fox paints them through the raw, gritty portraiture that is his signature.

Fox often asserts that his subject matter is arbitrary, realized more so by organic means of disseminating information—discovery, chance, environment—than by what he perceives as elitist preoccupations with content and its perceived value. “Painting isn’t about that for me,” he notes. In an age of algorithmic means of deciphering tastes, Fox remains committed to thematically painting on a human scale. He encounters his subject matter through walks, routines, and habits, keeping his images based on a kind of bartering system with the visual world, reflecting the primitive inflections of his works.

I.

Fox first came across the work of the Kellogg Brothers, widely collected nineteenth-century American lithographers based in Hartford, Connecticut, in a tattoo parlor. In their heyday, Kellogg images were printed by the thousands: lithographs “were ‘modern art’ not only because the process was a recent invention,” Nancy Finlay writes in Picturing Victorian America.[3] “They were also strikingly modern in their depiction of contemporary life.” In The Prodigal Son Returned to His Father, the well-known biblical story is sanitized via Victorian settings, as well- dressed bourgeoisie welcome the son into a picturesque garden and mansion. [4] In The Prodigal Son Reveling with Harlots, the titular character entertains a table of relatively tasteful Victorian ladies.[5] Such prints of the prodigal son decorated the walls of middle-class homes and offices throughout America.[6] “The prodigal son leaves home, fucks up, loses his inheritance, feels sorry for himself,” Fox explains of his interest in the prints. “Everybody had it in their house. It was the Marilyn Monroe poster of its day.”

Fox’s The Prodigal Son Sucks Dick for Crack at first smacks of rebellion in its treatment of its subject. But the fact that what is ostensibly sacred is rendered pulpy and raw in fact guides us closer to its source material. A forgotten symbol of the rise of middle class America—owned by new white-collar workers and housewives—gets recast as a glimpse into contemporary inequality and destitution. In contrast to the Kellogg’s delicate sensibility, Fox’s rendition is washed in thick, imprecise strokes, reflecting the world from which they were made, but drawing us far closer to the story’s deeper implications. With asphalt grays and earthy browns, Fox employs color just as lithography did as a brash, narrative technique. His streaky, impasto surfaces, too, call attention to the human hand, though the accumulation of the Kelloggs’ imagery is evident. Fox’s figures appear in Victorian dress, wearing masklike expressions, but now within Skid Row, next to Wholesale Plaza, near Fox’s studio. Elements of the scene appear out of place, as the son holds a penis disconnected from the body of his client, in anticipation of the act, rather than the fixed, and therefore safe, imagery of the Victorians.

In The Prodigal Son Sells Crystal on the Corner one similarly finds markers of modern-day life on Skid Row in the Rosslyn Hotel or the metal siding of a closed-up shop, a common signifier of nightfall. The interplay of primary colors on the men’s Victorian clothing and the metal siding unites these figures with their setting, as in their source material. Yet the color story also drives a larger point, that modes of exchange cannot be divorced from their surroundings. Fox describes the particular grayish brown as particular to the area, of grime and bleaching by the sun: “The feeling of the painting is coming from around here: The grayness, the brown-ness, and the gray concrete turning brown.” It is a scene distinctive of Skid Row, and of Fox’s perspective as both removed onlooker and local chronicler. A seemingly out-of-place red rose floats in the background in a brief moment of abstracted romanticism made abruptly poignant.

II.

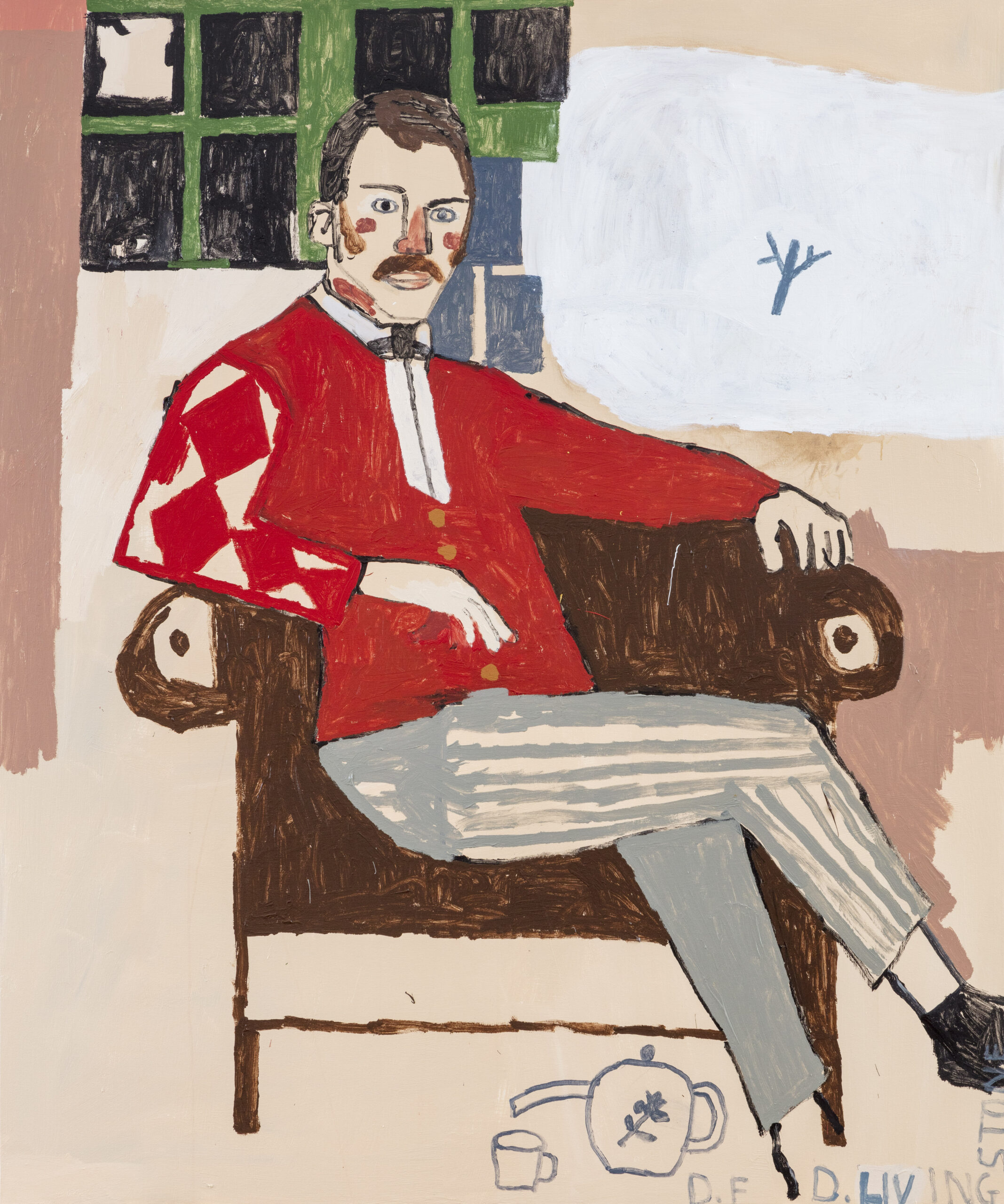

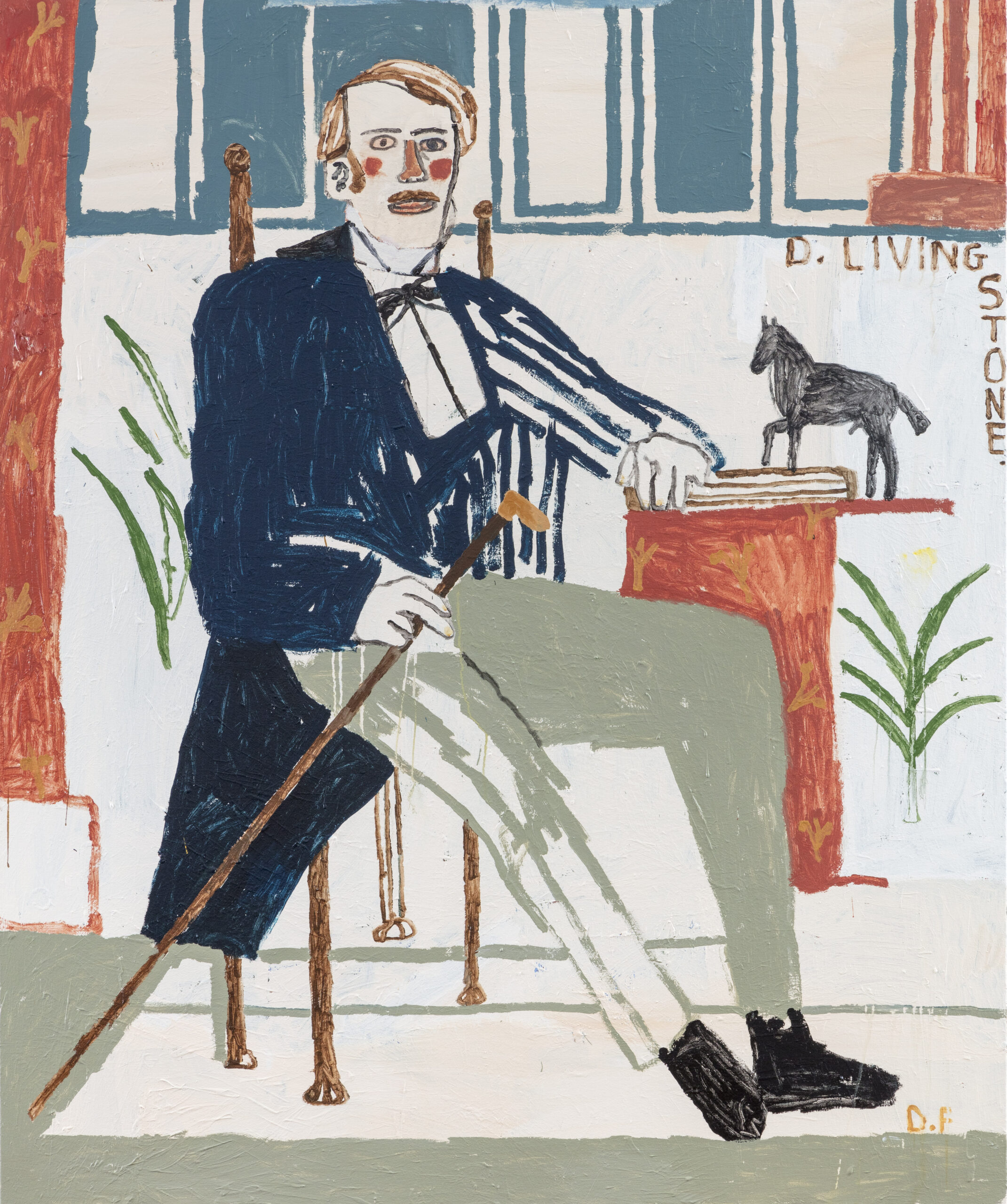

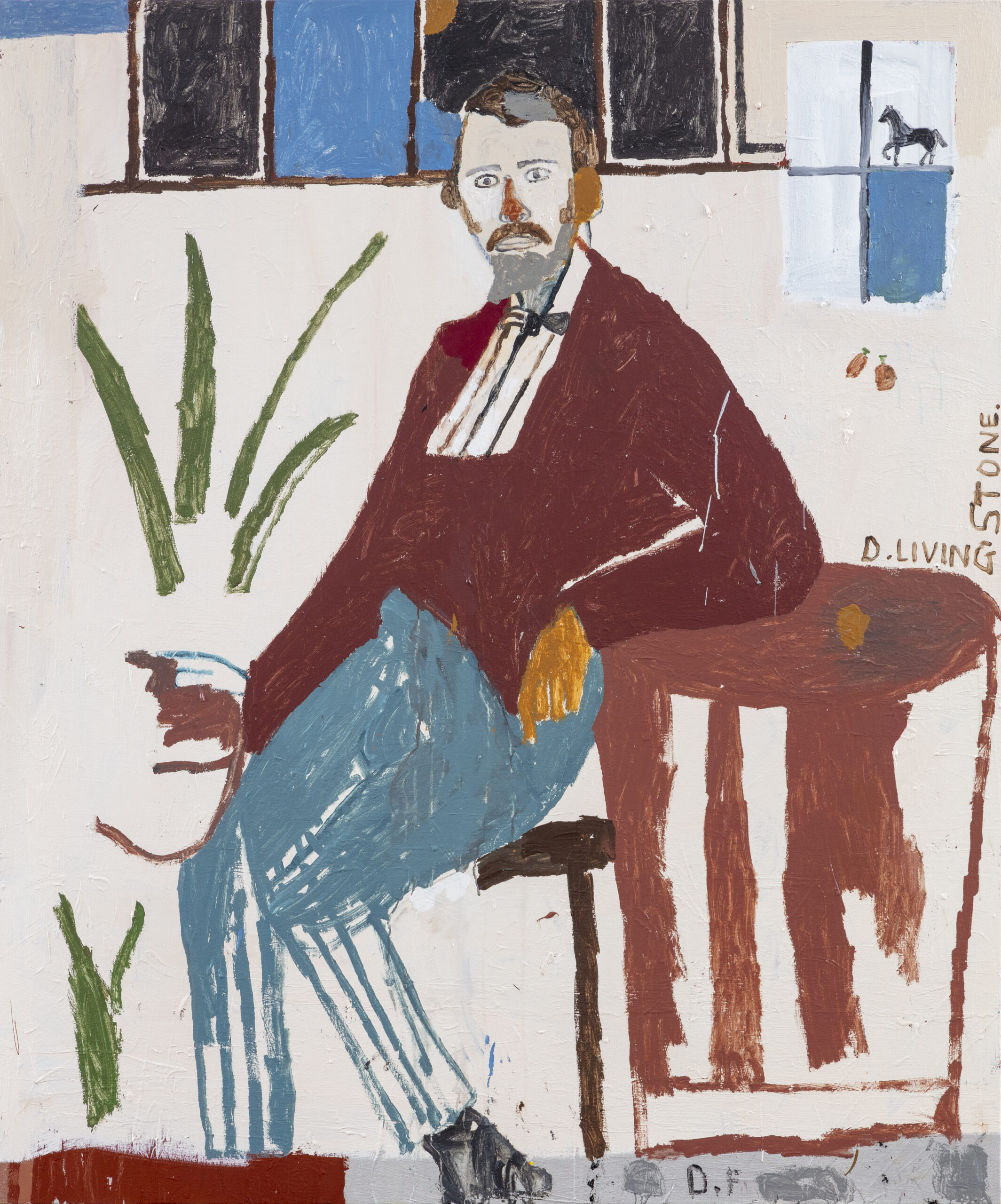

In another body of work on view, Fox has created a group of portraits of David Livingstone, what he calls one of his most concentrated series to date. Fox became fascinated with Livingstone after finding a vintage children’s book about him among used books in London.[7] “You just don’t see these kinds of images any more,” Fox notes of the simplistic vintage illustrations. “That looks like a painting to me.”

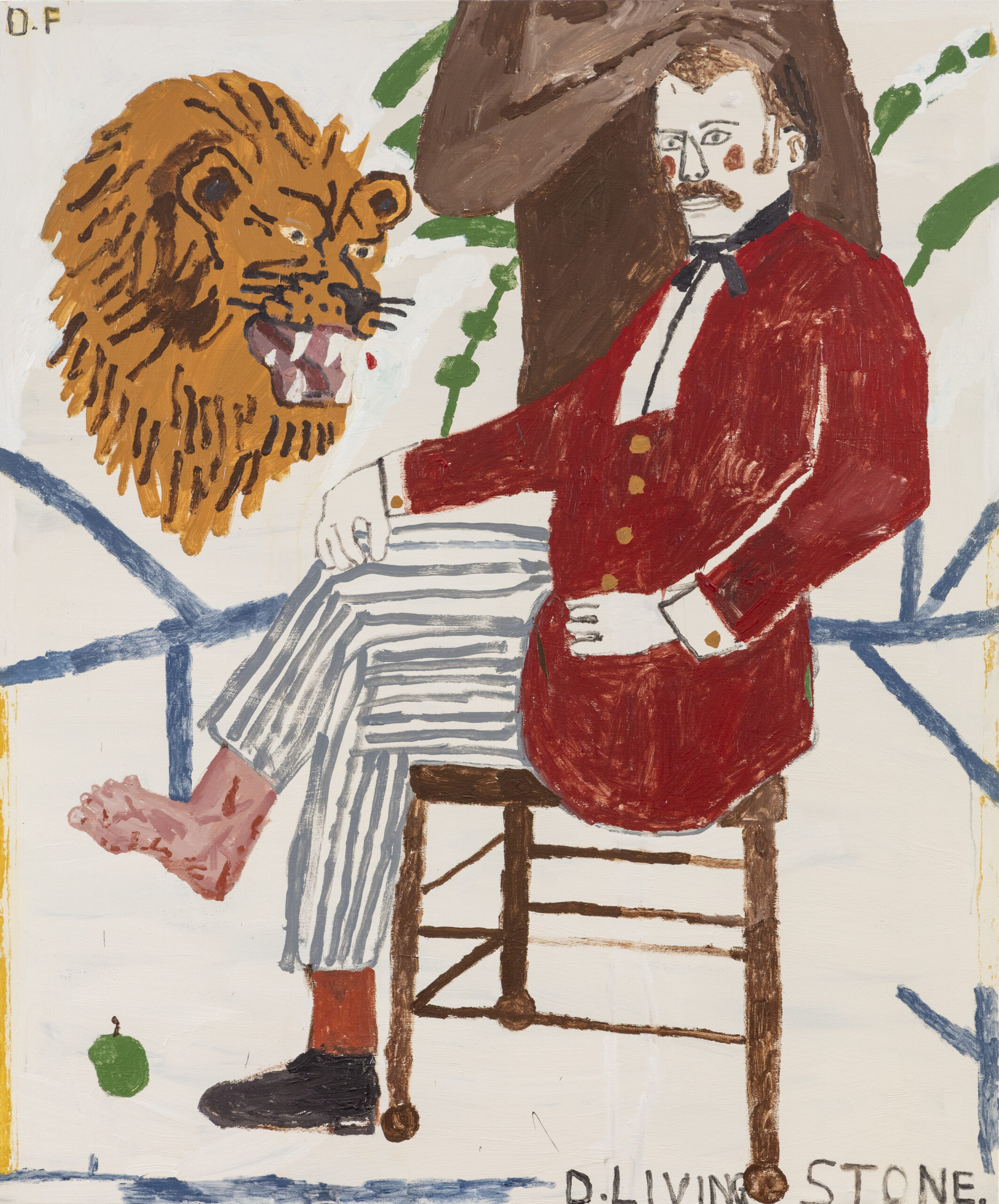

Livingstone was contemporaneous with the Kellogg Brothers, setting out as a missionary in the 1840s. Determined to find the source of the Nile, where his travels in Africa turned him into an abolitionist advocate, Livingstone was a celebrated hero of the Victorian era who closely embodied its ideals.[8] The seated portraits of Livingstone clearly delineate Fox’s own painterly concerns. As Fox notes, the composition of the seated male is nearly identical to his horse-and-rider images; thematically, the trope also depicts a man poised in relation to his quest. The seated male offers perhaps even more opportunity for play, in settings far less abstracted than Fox typically uses, though entirely ahistorical. Fox toys with images of hero worship, painting them in a manner that communicates the brutalism and labor intrinsic to their historical importance.

In Barefoot with Striped Suit, Fox makes use of flat planes of contrasting prints in a clear gesture at the portraiture of Matisse. The blood-red floor calls out the red stripes of Livingstone’s suit, streaky as scratches. The backdrop, at first glance a floral wallpaper, suggests a pitch-black night in the bush, with twinkling stars, all painted with jagged, transparent swatches. In the show’s titular painting Blood Spots on Apple Fresh, Fox similarly references Livingstone’s history through a number of symbols. Livingstone appears, again, a jungle-like setting, facing a lion—in reference to his own mauling by a lion in the 1840s—with infected feet, an ailment that plagued him as his health failed shortly before he died in present-day Zambia.[9]

A pair of portraits D. Livingstone as young man and D. Livingstone as an old man seem to depict the explorer in the same environment–a sparse, plant-lined modern space not unlike Fox’s studio–though Livingstone he died at barely sixty years old. In these bookend-like paintings, Fox underlines that his subject matter is simply that–matter–further attuning us to the painter’s choices. A portrait of refined heroism becomes realized as choppy strokes, with large sections of the body unfinished, as if still in progress. In The Banks of the Lualaba River, one of the most abstracted paintings on view, Fox brutally reimagines the site of a pivotal moment for Livingstone on his journey to the source of the Nile. On July 15, 1871, while Livingstone was famously lost to the outside world, he witnessed roughly 400 people massacred by slave traders in present-day Democratic Republic of Congo. The event left Livingstone too distraught to continue his search, and led him to return to what is now Tanzania, where he made contact with Henry Morton Stanley in their famous meeting.[10] In Fox’s hands, the scene is washed in a sea of red, with small details called out, embracing the brutality of a moment now lost.

III.

Fox says the Livingstone series stems from his earlier work Highline Cream about his grandfather, also a Scotsman, who went to Zimbabwe to become an architect. The enmeshing of personal history with collective mythology remains central to Fox, as he here collapses the dreams of the Victorian world into the present.

Fox’s paintings have been described as “abrasive” and “confrontational”; the pictures, however, have empathy, in their roughened, painful yet simplistic, often childlike manner.[11] In paintings such

as The Nickel, Fox returns to the horse-and-rider motif he has used throughout his career. A traditionally dressed figure races through a seemingly natural landscape, with suggestions of flora and fauna, offset by a red sign announcing “The Nickel,” the colloquial name for Skid Row, given that the area is centered on 5th Street. Fox’s organic exchange with his environment often inspires such singular imagery, as he continually makes the case that history is not random, only repetition.

Self-taught artist Danny Fox was born in St.Ives, Cornwall, UK, a seaside town made famous by its numerous artist residents. Despite moving from the town many years ago, Fox’s cornish lineage remains visible in his work. After setting his studio in Los-Angeles Fox recently moved back to the UK. The exhibition gallery of Sotheby’s, Sotheby’s SI2 dedicated two solo exhibitions to Danny Fox in New York and Los Angeles (2016). Fox is part of Iconoclasts, a group exhibition at Saatchi Gallery in London (September 2017 – March 2018)

[1] Meares, Hadley. “Why Skid Row—The Nation’s Largest Homeless Encampment—Formed In Downtown LA.” Curbed LA, 2018, https://la.curbed.com/2017/12/14/16756190/skid-row-homeless-history

[2] “History Timeline – Skid Row Housing Trust.” Skid Row Housing Trust, 2018, http://skidrow.org/about/history/.

[3] Finlay, Nancy, and Kate Steinway. Picturing Victorian America. Middletown, Wesleyan University Press, 2010.

[4] Kellogg and Co., D.W. “The Prodigal Son Returned to his Father.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ca. 1830-40.

[5] Kellogg and Co., D.W. “The Prodigal Son Reveling with Harlots.” Smithsonian National Museum Of American History, Washington D.C., ca. 1838.

[6] “The Kellogg Brothers: Lithograph Printmakers From Hartford.” Philadelphia Print Shop Ltd., 2018, http://www.philaprintshop.com/kellogg.html.

[7] Peach, L. du Garde. David Livingstone (An Adventure From History) … With Illustrations By John Kenney. Wills & Hepworth, Loughborough, 1960.

[8] Dugard, Martin. Into Africa. New York, Doubleday, 2003.

[9] Livingstone, David. The Life And African Explorations Of Dr. David Livingstone. New York, Cooper Square Press, 2002.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Della-Ragione, Joanna. “Spotlight: Danny Fox | Artinfo.” Artinfo, 2018, http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/1358450/spotlight-danny-fox.

UP

UP