PRESS RELEASE

Zidoun Bossuyt Gallery Paris presents YoYo Lander: A Big Romance and Nate Lewis: Still Tuning A Current, which feature the artists’ continued explorations of color, form, process and the body.

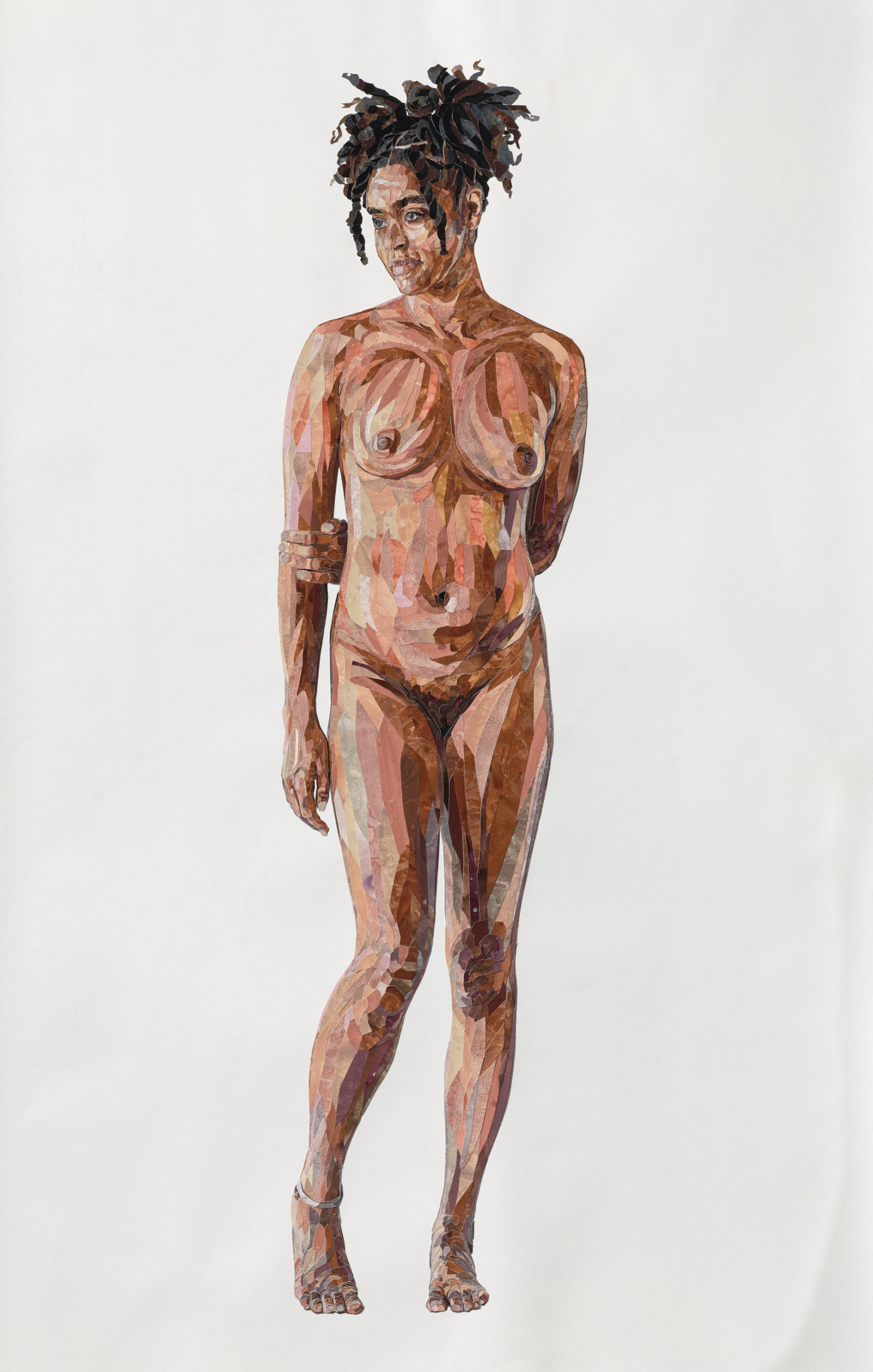

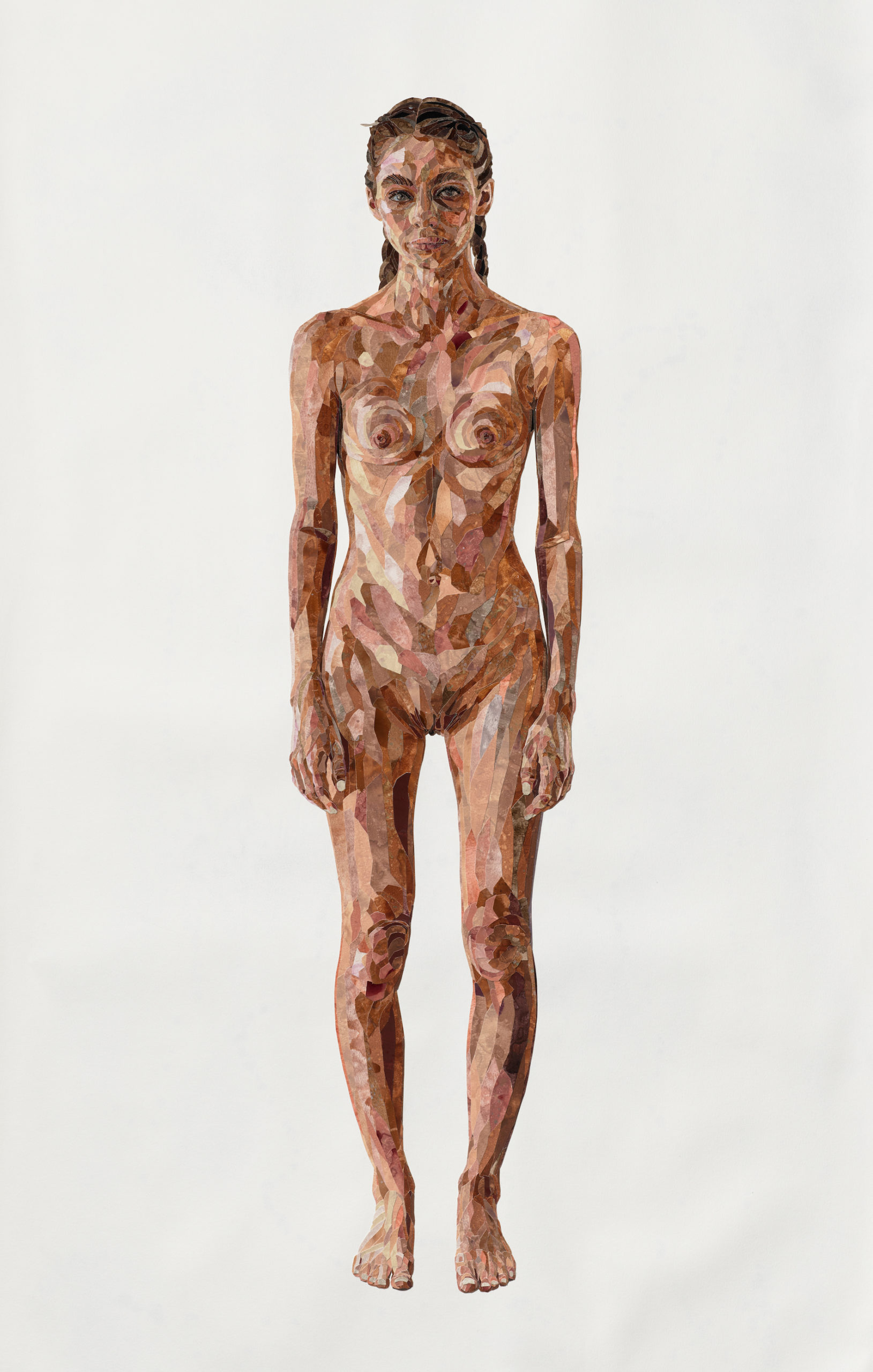

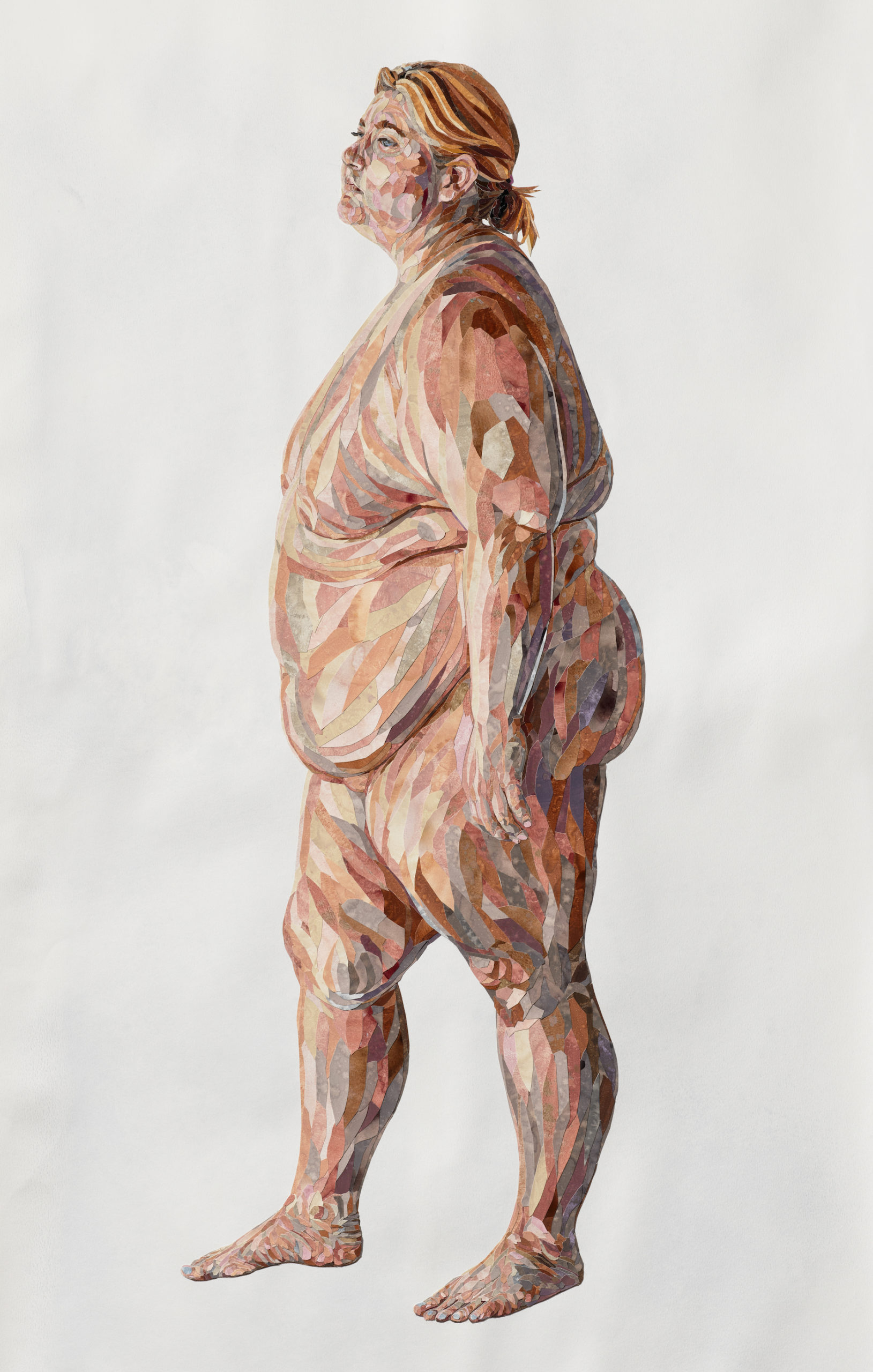

YoYo Lander has called her work a journey into the “visceral and expressive” nature of the “essence of humanity.” The richly-pigmented and densely-detailed watercolor collage works Lander created for A Big Romance seek to uncover the organic nature of simply being and the beauty that comes with self-acceptance. The title alludes to the most important relationship of all: the one we have with ourselves. With the understanding that all bodies are political, the artist’s process begins with photographing subjects who are outside of the realm of the body types reified in contemporary art history and culture. Lander’s chosen subjects exude strength and self-possession.

Nate Lewis continues his exploration with diagnostics languages, figures in motion, and music with new dimensions of textural intervention. Still Tuning A Current introduces a new embossment technique featuring a musical score of the renowned 20th century Black American composer William Grant Still. Lewis sculpts his signature cuts, folds, and picks through his paper tableaus. Like Lander, the artist’s process begins with still photographs of dancers and martial artists moving through space. In these new works, the figures seem to dance to and through Still’s musical score, freeing them from the confines of the pictorial frame and space, and time themselves.

YoYo Lander: A Big Romance

Lander’s process is one of intense looking. The women depicted in A Big Romance are inimitable, magnetic. She desires to catch them in their most natural and honest states. Each collage work is a coalescence of multiple still photographs captured by the artist. An arched back from this one. A shoulder rounded just so from that one. Every element of Lander’s collages is meticulously approached. With watercolor paint she mixes and blends countless slivers of watercolor paper to reconstruct the figures of her sitters. She seamlessly recalls and renders dozens of browns, grays, pinks, purples, and yellows in the undertones in each subject’s skin.

The colors by themselves almost feel muted. With incredible attention to detail, Lander carefully reconstructs her sitters. Despite the fact that Lander has perfected this technique over a number of years, the quality of it still manages to read as alchemical. Together the strips of watercolor paper take on a fantastically dynamic energy through their kaleidoscopic range. Though she rends paper, Lander’s gestures are a means toward a kind of radical wholeness. Her small gestures and sculptural tears make evident every sinew, the electrical impulses in every muscle, the ease and tension in the fascia cradling them. She renders their eyes expertly, gently; somehow translating what feels like all the light in the world with each piece of hand-dyed paper into the figures’ eyes.

It is particularly well-evidenced in Morgan (2023). Morgan’s eyes are piercing. In spherical arcs, shadows and shades of brown, green, and gray, Lander manages to make the subject’s eyes prismatic. They recall hyper naturalistic details of the Renaissance era seen in the work of painters like Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Jan Van Eyck, and others. Considering that those works are almost exclusively made with oil paint, the artist achieves something with watercolor that is thoroughly uncommon and thus revelatory. Perhaps there are slight glimpses of it in British painter Elizabeth Murphy’s 19th century Romantic period watercolors, and in American painter John Singer Sergeant watercolor period at the turn of the 20th century; but nothing quite like where Lander takes her technique. Because she desires to depict her sitters’ equanimity and self-love, that sole soft focus of her tableaus allows her to get there. You cannot teach this kind of transmutation. It is found through experimentation and a quest to find the magical inside of both one’s self and the subject.

Nate Lewis: Still Tuning the Current

The works in Still Tuning the Current, find Nate Lewis at play, returning to the early methodologies at the root of his artistic practice. His hand and mind are unencumbered by the restraint he has focused on for the last several years. There is a looseness in this work that he has not allowed himself in recent years. He is not over-intellectualizing but rather listening and feeling the work and how it may want to make its way into the world. It is an open, poetic process that allows the work itself to be responsive and sentient of itself. He is in flow with himself and the energy of the moment, riding the current to wherever it may lead him.

A decade ago, Lewis began using echocardiograms and sheet music in his art works while working as a nurse in an Intensive and Critical Care unit of a hospital. In the interceding years, he has pushed through what he has called a “language of examination,” to give way to what I think is a larger methodology of rhythm, tonality and texture. Past installations have also included commissioned compositions, and interpolations of existing ones. At the heart of the diagnostic tools that have so long supported Lewis’ practice is a correlation to reading a baseline rhythm. It is indeed an integral element to their functionality. His natural affinity for music works hand in hand with this.

Within that critical site of return for Lewis is the music of the barrier-breaking 20th century Black American composer William Grant Still. Still’s professional life was marked by many distinctions. He was the first American composer to have an opera performed by the New York City Ballet. His first symphony composition, Symphony No. 1 “Afro-American” (1930), was the first complete symphony created by a Black American to be performed in its totality, and until 1950 later was the most widely performed symphony by an American composer. He blended the sensibilities, “harmonic and rhythmic language of jazz and blues to portray the sense of ‘otherness’” often germane to the Black American experience. The composition is also featured in Lewis’ first video work, Navigating Through Time (2020), juxtaposed against Chopin, a chorus of bells, and a recording of the 1910 “Fight of the Century,” the first professional interracial boxing bout.

Reintroducing the composition in another form, Lewis commissioned an embossment of a movement of Still’s Symphony No. 1 invoking the mélange of the cultures integral to his own work. Moving away from frottage and embossment with found objects, integrating this new element, the texturality created by the embossment, and with the artist’s signature gestures of hand sculpting on images of Black bodies in motion feels dimensional and almost centripetal – a force that acts on bodies and objects making them move in curved lines through space. In Synchronicity in the Storm (2023), the picks, slices, opening up the paper together with impressions of the musical notations call to mind mapping. They motion toward a critical topography of possibility, a reading of the places we find ourselves and what might happen if we allow our sensitivities to lead the way.

UP

UP