Zidoun-Bossuyt Gallery is pleased to present Jeff Sonhouse’s new solo show.

PRESS RELEASE

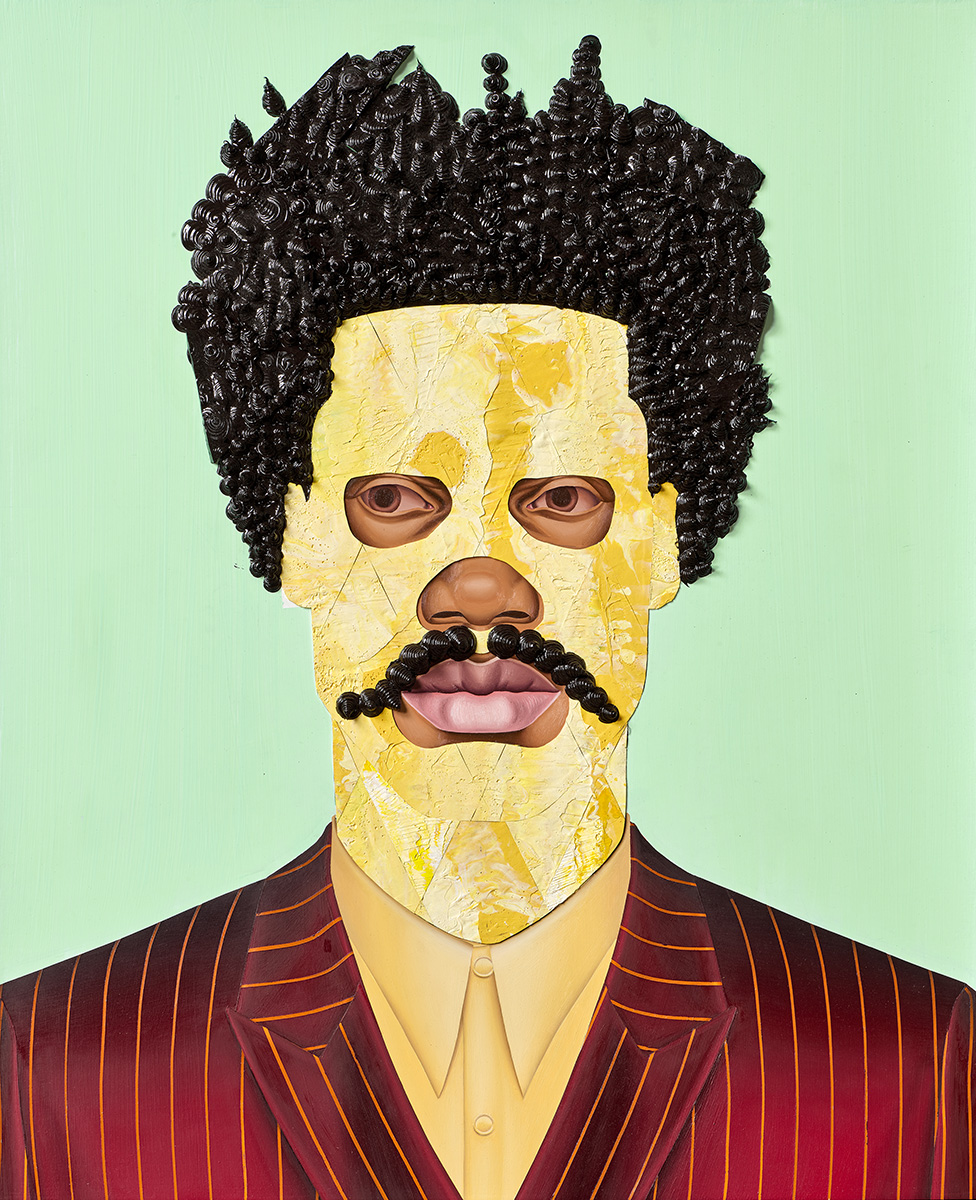

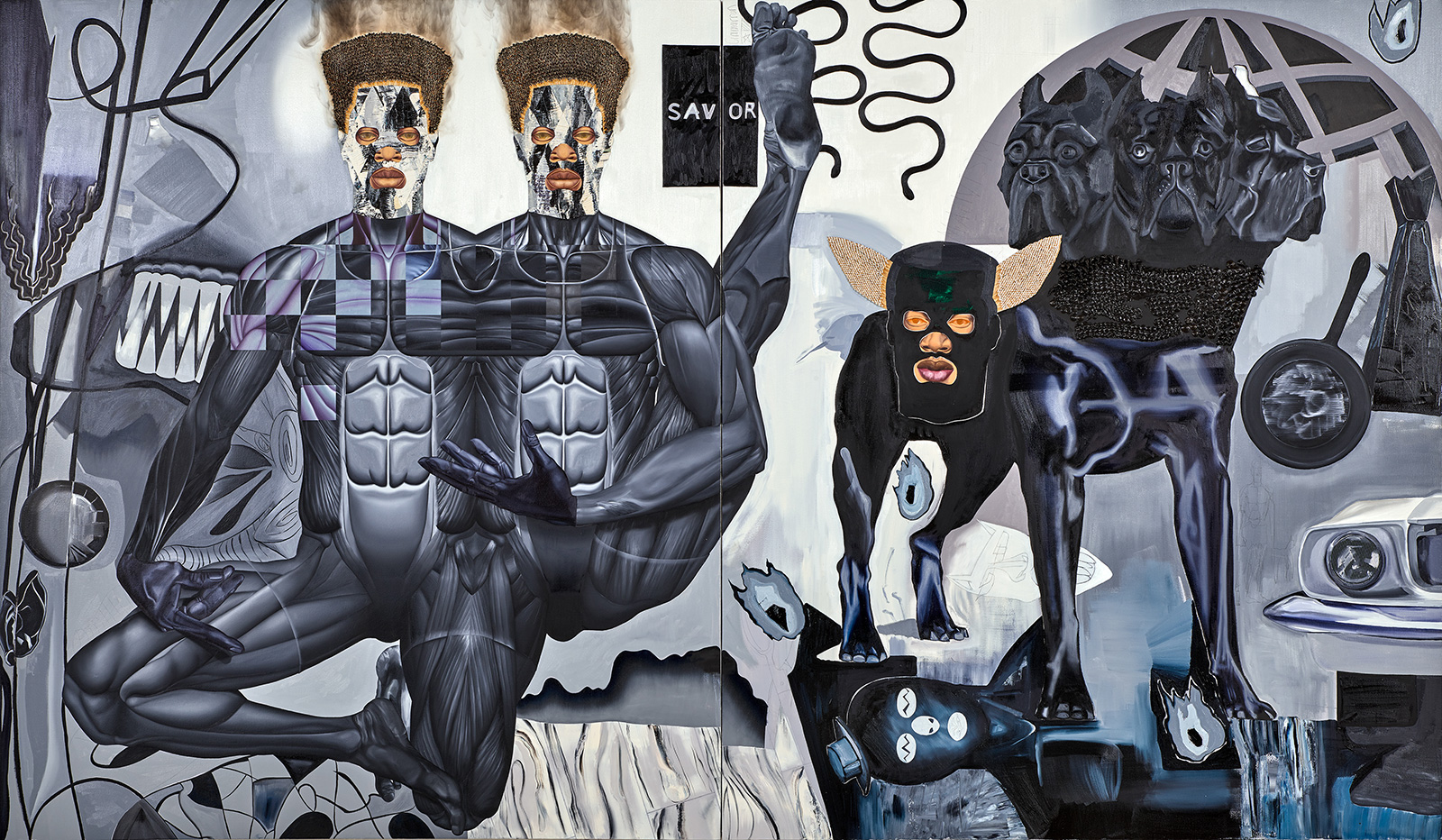

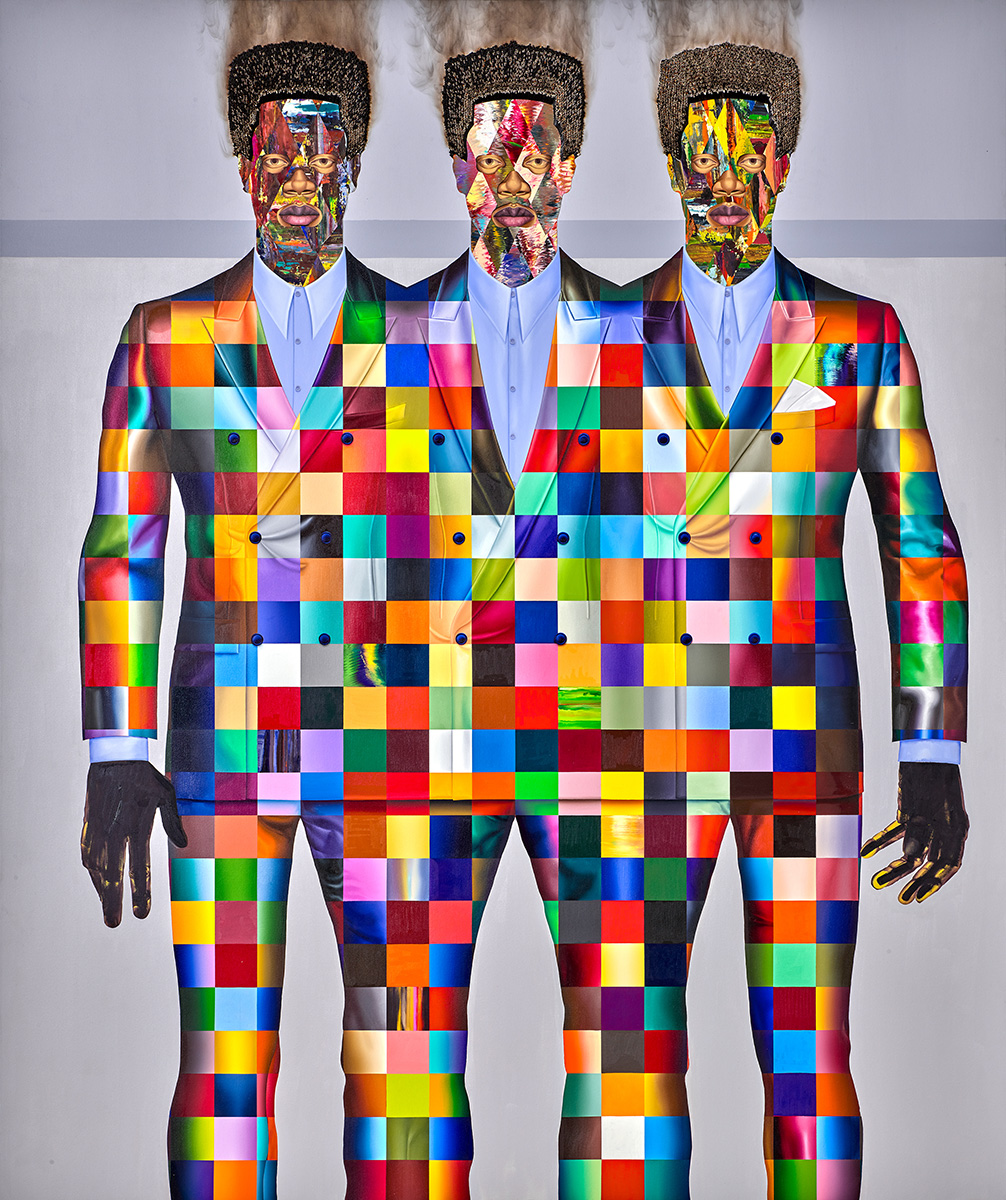

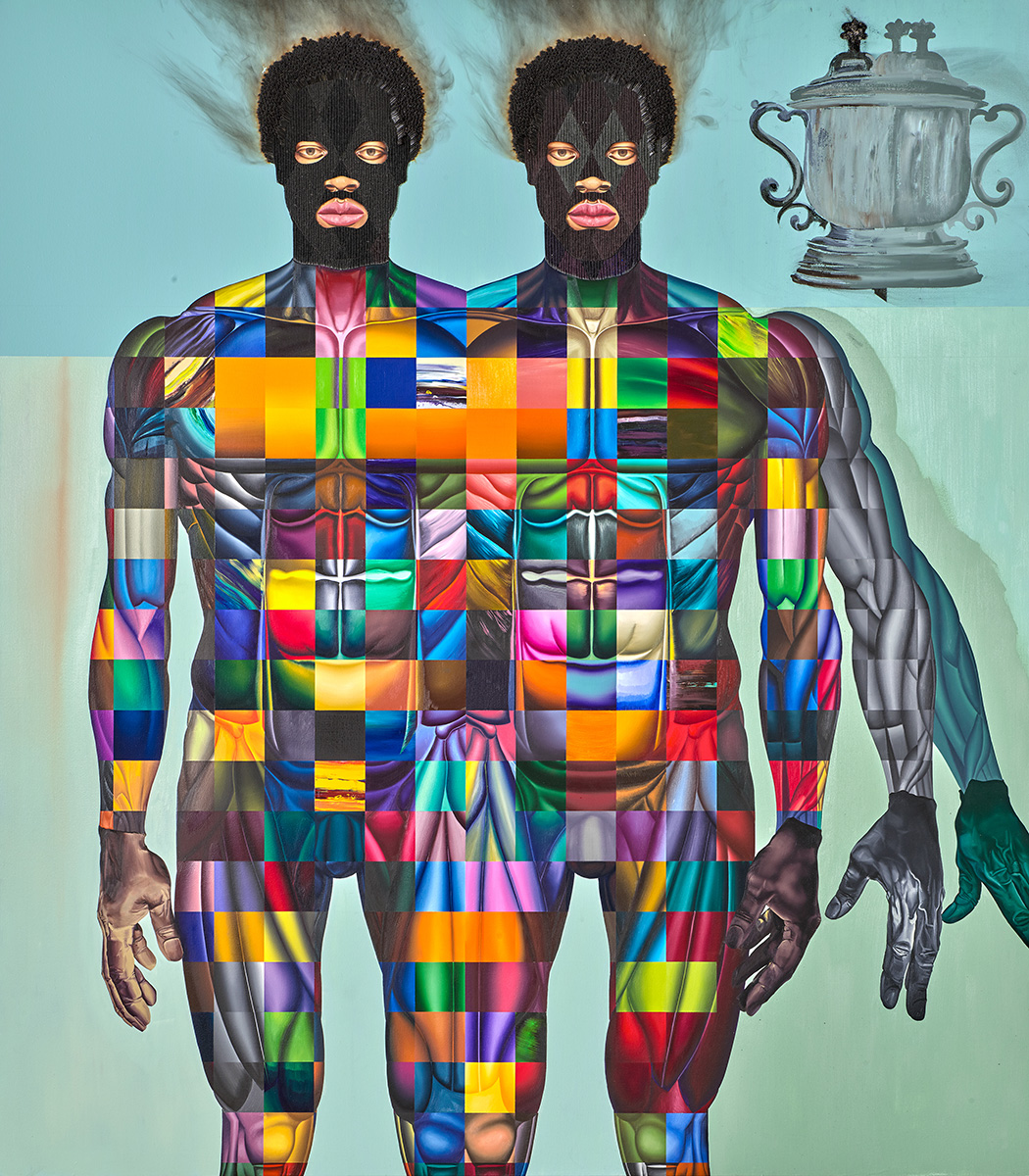

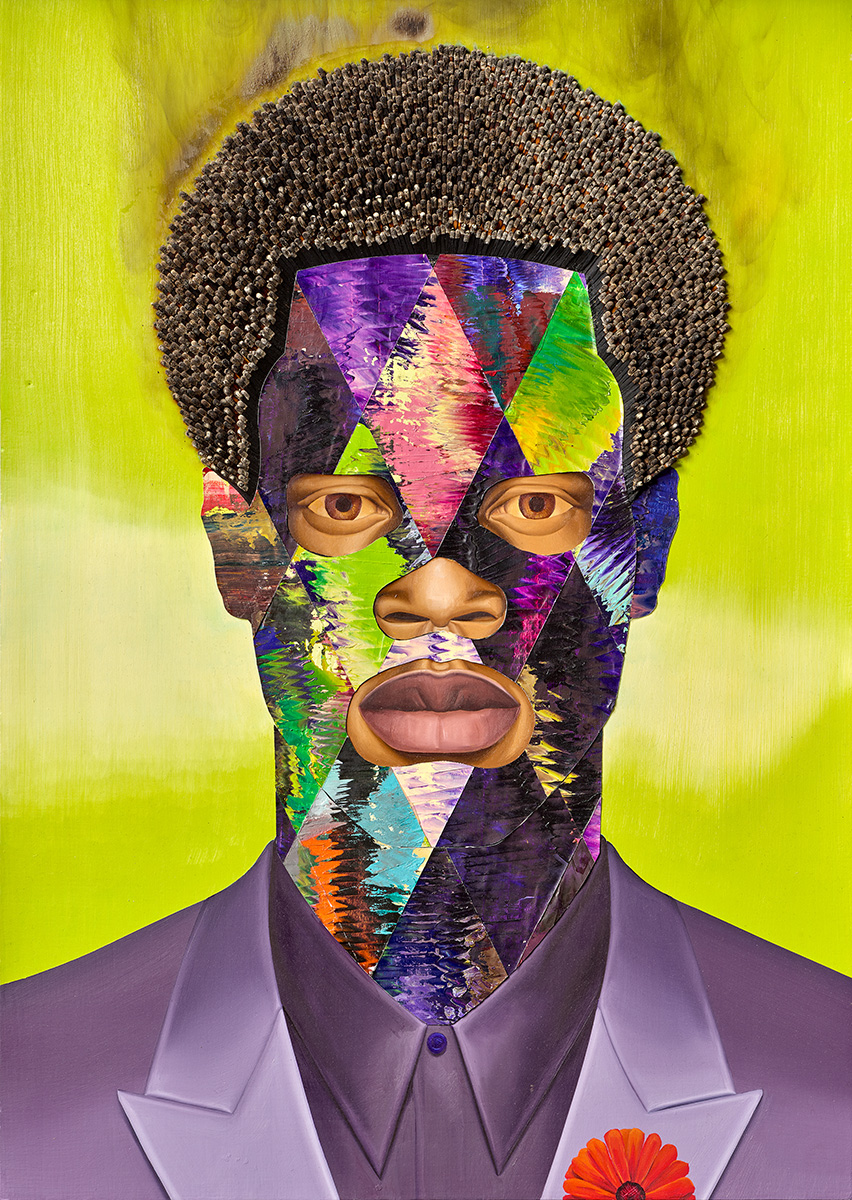

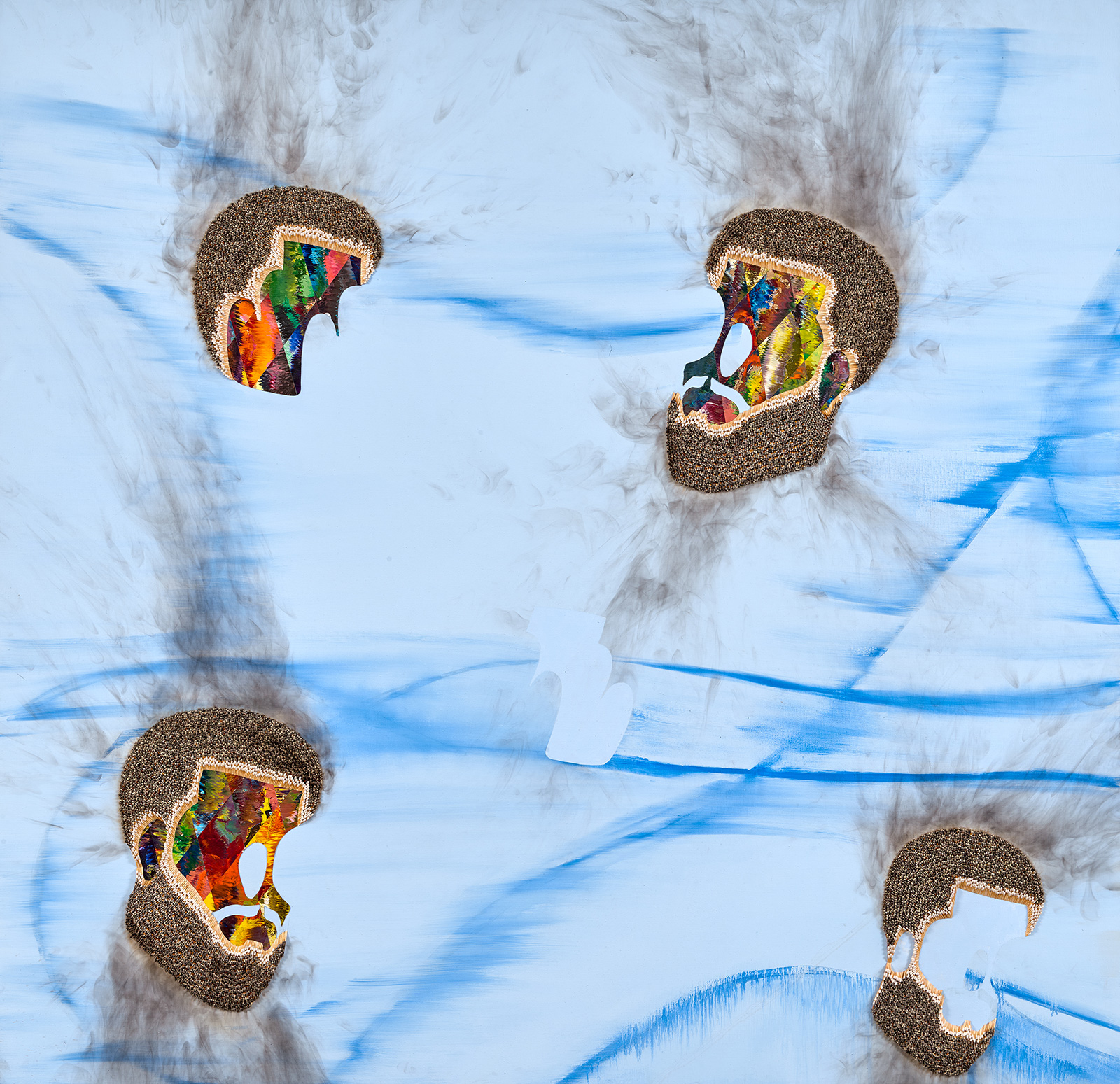

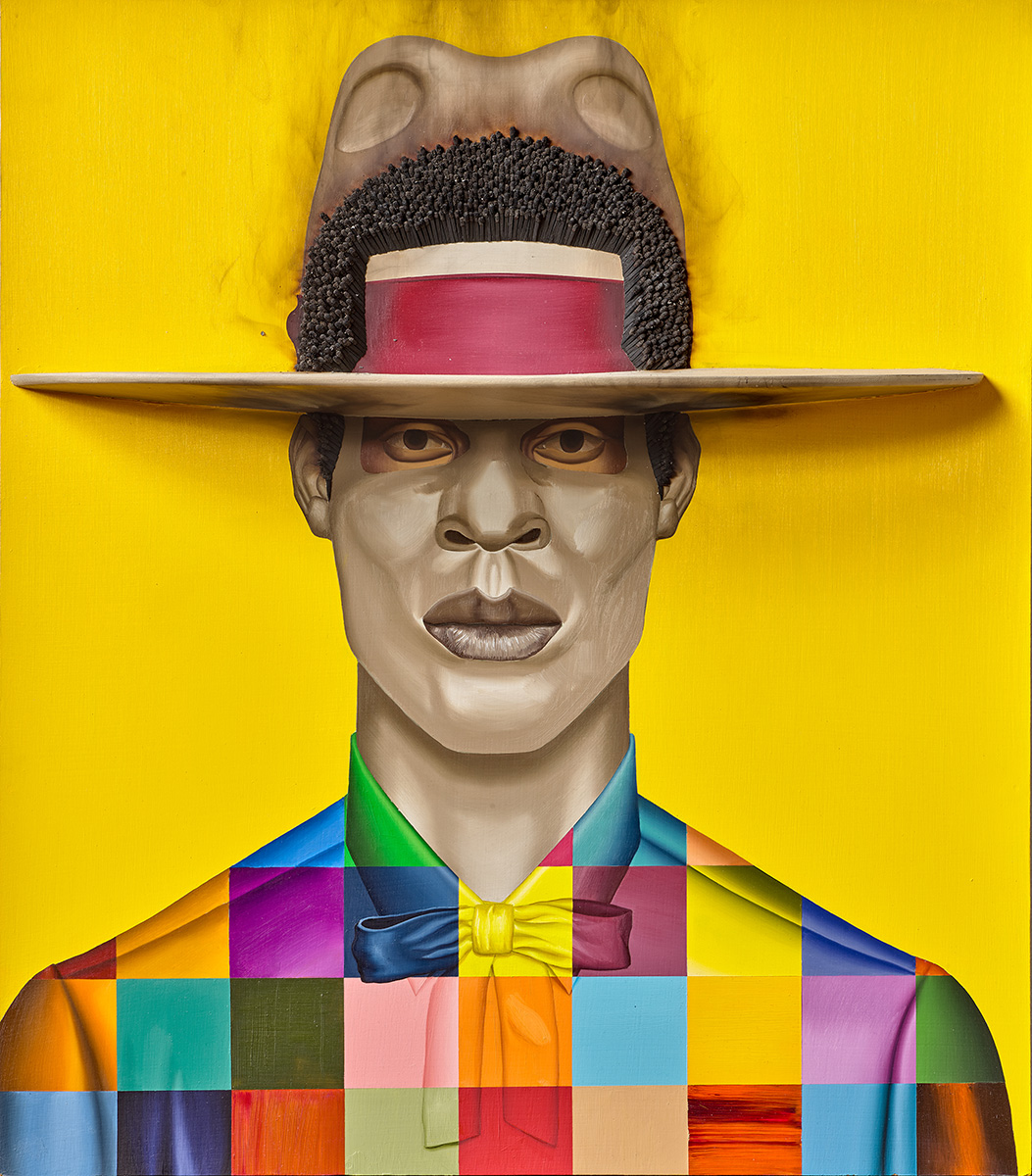

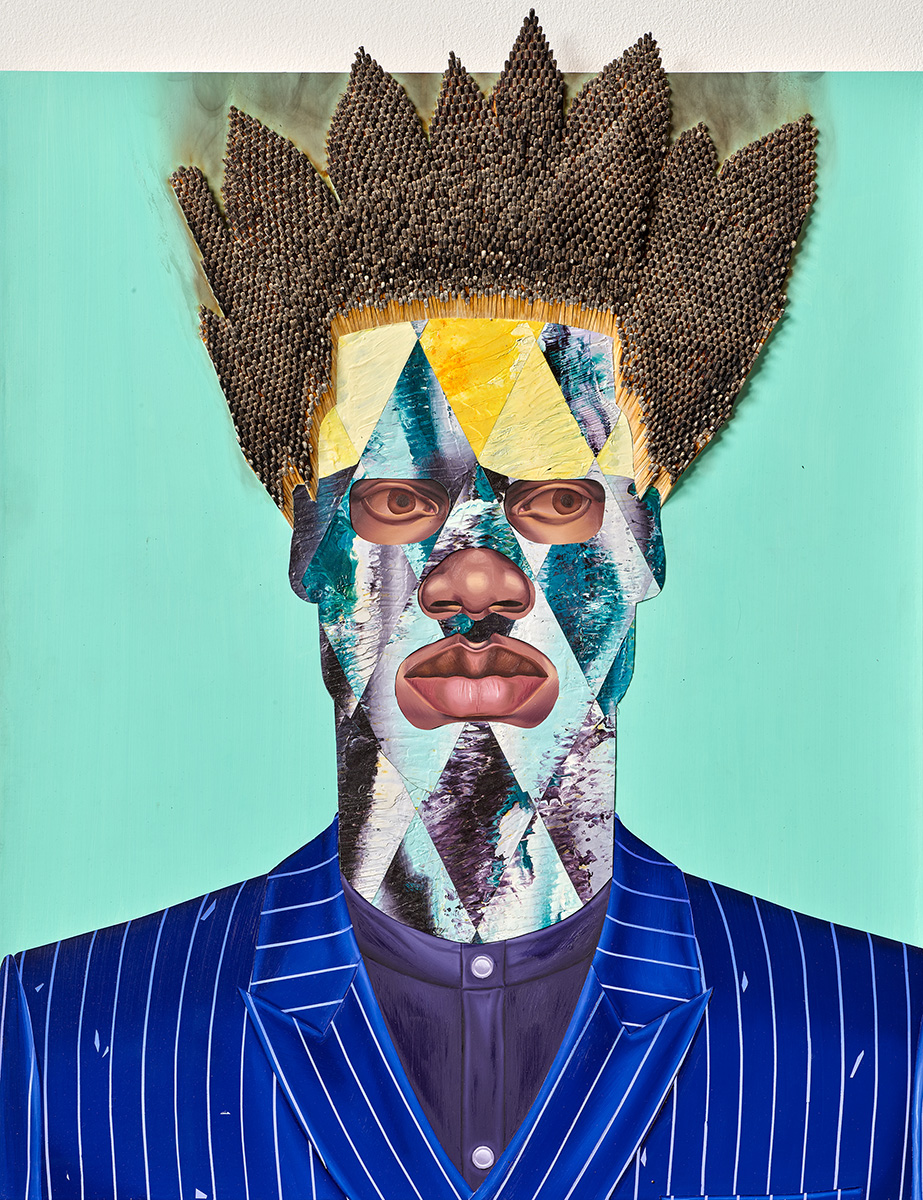

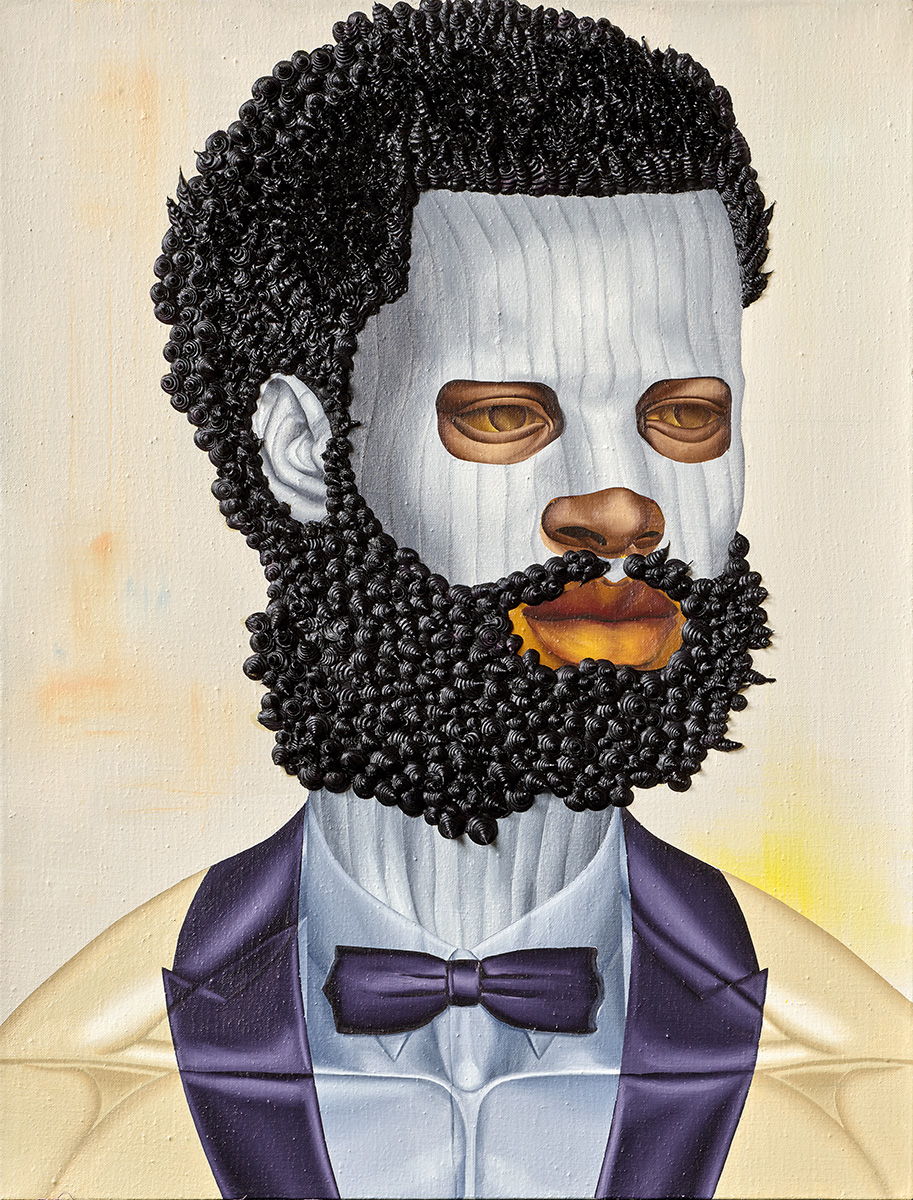

Jeff Sonhouse’s (American, born 1968) portrait-style paintings of Black figures are a unique fusion of imagery and materials that challenge traditional modes of representation. Sonhouse contemporane- ously questions established art historical concepts and compositions as they relate to the figure with a distinct pull toward developing his own mythologies in painting. Through his distinct use of abstract pa”erns, masking, and the doubling/tripling and disembodiment of the figure he forges pathways to expanded forms of representation. His composite imagery includes aspects from Western art histori- cal portraiture, contemporary men’s fashion magazines, images of friends, and self-portraits. These in- fluences align with the complex critical ideas drawn from what art historian Darby English (American, born 1974) acknowledges as a more modern approach to the reception of art, grounded in a sense of intimacy while taking a spectrum of perspectives into consideration.

Sonhouse primarily makes stylized portraits of Black figures: floating heads, busts, and full-length, single, double, and group portraits, mostly of men. They o#en wear formal single-breasted suits in varying bright colors with pinstripe and harlequin pa”erns. These electric colors extend into the lush backgrounds of many of his portraits. He then adds materials like matches, steel and copper wool, feathers, shells, and stones to emphasize details on the figure’s hair, eyes, and accessories. Sonhouse’s portrait style, like that of Benny Andrews (American, 1930–2006), Romare Bearden (American, 1911– 1988), Barkley L. Hendricks (American, 1945–2017), and Betye Saar (American, born 1926), challenges the singular perspective of Black artists making work solely about Black life and more closely aligns with the long arc of artists engaging in Western art history’s scope of portraiture. Tremendous critical work in writing and exhibitions has been done by art historians, critics, and curators such as Isolde Bri- elmaier, Susan E. Cahan, Valerie Cassel Oliver, Darby English, Michelle Glenn, Thelma Golden, Rujeko Hockley, Christine Y. Kim, Catherine Morris, Lowrey Stokes Sims, Zoé Whitley, and others to push for the recognition of Black artists from the onset of the development of American art.

In the studio, he “is in good competition with art history”—with the arc of figuration and American abstraction—in that he employs aspects of Western art and utilizes its structures and motifs that are “imbedded in [his] consciousness” allowing him to “forge new space for [his] figures to exist in, to be found in that arc.” His work also engages within the context of representation—an examination of African American identity, masculinity, and culture—expressed in the formal, material, and con- ceptual tension in his works. Sonhouse earned his B.F.A. from the School of the Visual Arts in New York in 1998 where he met artists Alice Aycock (American, born 1946), Ellsworth Ausby (American, 1942–2011), Carroll Dunham (American, born 1949), and Jack Whitten. He was exposed to the practices of Aycock’s surrealist gestures defying any one particular narrative, Ausby’s hard-edged geo- metric abstraction in multiple layers and patterns, Dunham’s explorations of the relationship between abstraction and figuration, and Whitten’s formal experimentations with abstraction and its ability to express social, political, and cultural references. For two summers, Sonhouse worked in Whitten’s studio, building upon keystones of art history-pattern, form, and material—yet effacing expected methods like a palimpsest. His recognition of bodied beings as composite figures is a significant contribution to the scope of figuration.

Erin Dziedzic

Director of Curatorial Affairs

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art

UP

UP